Under Ludum Dare 31 I used the Piston/ai_behavior library first time “for real”. This is what I learned!

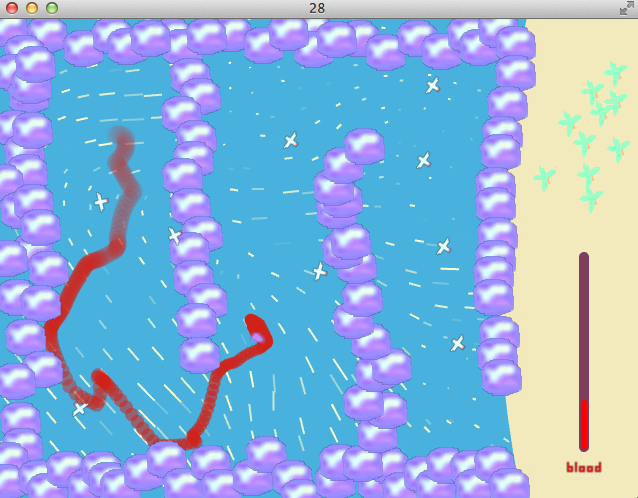

Four times a year there is a Ludum Dare competition, where you make a game within 48 hours. Here is a screenshot of the game I made, Sea Birds’ Breakfast:

The sea birds in these games are programmed by using something called “AI behavior trees”. While this sounds scary, it is actually easy to use.

A history of the AI behavior library

The project started out as an attempt by Coeuvre to model event logic using the observer pattern. This did not work very well with Rust’s borrow checker. Therefore, I took the features Coeuvre wanted, and built an expression tree around it. In that process I start to think of old problems I had with event programming.

In GUI programming for complex interfaces, one event might trigger another, which triggers the first one, and the entire program hangs. I wanted a way of programming event logic where you could see the infinite loops. As shown below it can still happen, but it is a lot easier to find out why.

What I did not expect to find, was a way to make building blocks of logic that runs forever. Those are not loops that causes the program to hang, but they never terminate in the logical sense. This is possible because it gets updated in incremental time steps. In normal programming you have to break out of infinite loops, but when you have parallel semantics, you can add the loop to another one that controls the flow from the outside.

Then I read an article about AI behavior trees, and found out that by combining failure tolerance and parallel semantics, we would cover both event logic and AI game logic. It was very time consuming to craft out the building blocks, but eventually it was done.

Then, after weeks of work, the problem was that nobody knew how to program with it!

Coeuvre started the sprite library, which is the first case of “real world” usage. It uses AI behavior trees to animate sprites, where the behavior is something you can “play” and “pause” etc.

How it looks like in code

Here is the constructor of SeaBirds:

impl SeaBirds {

pub fn new() -> SeaBirds {

use piston::ai_behavior::{

While, Action, WaitForever, WhenAny, Wait, Sequence

};

let circling = Action(Action::Circling);

let circle_until_player_within_distance =

Sequence(vec![

While(box Wait(5.0), vec![

circling.clone()

]),

While(box Action(Action::PlayerWithinDistance(50.0)), vec![

circling.clone()

]),

]);

let give_up_or_attack = WhenAny(vec![

Action(Action::PlayerFarAwayFromTarget(100.0)),

Sequence(vec![

Action(Action::PlayerWithinDistance(10.0)),

Action(Action::AttackPlayer(0.1)),

])

]);

let attack_attempt =

While(box give_up_or_attack, vec![

Action(Action::FlyTowardPlayer)

]);

let behavior = While(box WaitForever, vec![

circle_until_player_within_distance,

attack_attempt,

]);

SeaBirds {

birds: Vec::new(),

behavior: behavior,

}

}

}

As you can see from the code, a behavior tree is constructed by putting together smaller blocks.

There are blocks that come with the library, such as Wait(5.0) which means “wait 5 seconds”.

The Action block is used to do custom behavior, for example, Action(Action::FlyTowardPlayer).

Each sea bird stores a “state” of the behavior:

pub struct SeaBird {

pub pos: [f64, ..2],

pub dir: [f64, ..2],

pub target: [f64, ..2],

pub circling_angle: f64,

pub state: ai_behavior::State<Action, ()>,

}

The last part to make this work, is to describe how each action updates:

state.event(e, |_, dt, action, _| {

match *action {

Action::Circling => {

let angle = *circling_angle;

let angle_pos = add(*target,

scale([angle.cos(), angle.sin()], circling::RADIUS));

*dir = normalized_sub(angle_pos, *pos);

*pos = add(*pos, scale(*dir, dt * SPEEDUP * circling::SPEED));

let diff = sub(angle_pos, *pos);

let diff_len = len(diff);

if diff_len < circling::ADVANCE_RADIUS {

*circling_angle = angle + _360 / circling::N;

}

(ai_behavior::Running, 0.0)

}

Action::PlayerWithinDistance(dist) => {

let diff = sub(*pos, player.pos);

if len(diff) < dist {

(ai_behavior::Success, dt)

} else {

(ai_behavior::Running, 0.0)

}

}

Action::PlayerFarAwayFromTarget(dist) => {

let diff = sub(*target, player.pos);

if len(diff) > dist {

(ai_behavior::Success, dt)

} else {

(ai_behavior::Running, 0.0)

}

}

Action::FlyTowardPlayer => {

*dir = normalized_sub(player.pos, *pos);

*pos = add(*pos, scale(*dir, dt * SPEEDUP * circling::SPEED));

(ai_behavior::Running, 0.0)

}

Action::AttackPlayer(val) => {

player.state = player::State::Bitten(::settings::player::BITTEN_FADE_OUT_SECONDS);

blood_bar::decrease(val);

(ai_behavior::Success, dt)

}

}

});

Each action returns Success, Failure or Running and the number of seconds left of the update time delta.

For example, FlyTowardPlayer never succeeds or fails, it always returns (ai_behavior::Running, 0.0).

On the other hand, AttackPlayer returns immediately, so it does not “spend” any time by returning (ai_behavior::Success, dt).

Summary:

- Create a behavior tree (how the sea birds behave)

- Store a state per instance of the behavior (what the sea bird does in the moment)

- Describe how custom actions gets executed (how the sea bird interacts with the world)

That is all you need to use the library, and once you get used to this setup, you can combine it with more powerful patterns.

A sea bird attacks

When a sea bird started attacking me, it suddenly hang the entire program. First I thought this was a bug in the AI library, but the logic flaw was in the sea bird behavior.

What I found out, is that there was no pause after attacking the player. The sea bird went immediately from attacking to checking the distance and then back to attacking. Because neither action consumes time, it ran in an infinite loop. The circling logic was as following:

let circle_until_player_within_distance =

Sequence(vec![

While(box Action(Action::PlayerWithinDistance(50.0)), vec![

circling.clone()

]),

]);

I solved this by duplicating the circling loop and combining them with a sequence:

let circle_until_player_within_distance =

Sequence(vec![

While(box Wait(5.0), vec![

circling.clone()

]),

While(box Action(Action::PlayerWithinDistance(50.0)), vec![

circling.clone()

]),

]);

The only difference between two loops is the condition. Now, after the sea bird attempted an attack, it waits 5 seconds before it can attempt another one.

Unlike a while-loop in “normal” programming, the body of the loop runs in parallel with the condition. It runs until the condition terminates or when the body fails. If the condition succeeds, then the entire loop succeeds, but if it fails or the body fails, then the entire loop fails.

It is also possible to express the same behavior another way (for this particular case):

While(box Sequence(vec![Wait(5.0), Action::PlayerWithinDistance(50.0))]), vec![

circling.clone()

]);

The circling behavior runs forever, neither has it a beginning or end, so it does not matter if two follow each other instead of one.

AI behavior trees vs alternatives

It worked very well for something I had to code up quickly. There are other ways to do the same, for example by using finite state machines or an entity/component system.

I imagine that when working on a state machine, it would be terrible hard to do any kind of parallel behavior, and if I wanted to join two states I would likely mess up the control flow.

If I were to use an entity/component system, I would have to enable/disable the components that the systems uses for behavior, and this might not be as flexible.

A state at a given moment is described as multiple paths through the behavior tree. This is like adding another dimension to normal programming. While it easy to use on the surface, there could be cases where this leads to a problem.

It is still at the experimental stage, for but some problems I believe this becomes a powerful tool.